“Clean that up,” she hissed, holding a half‑spilled caramel macchiato like it was evidence in a felony case.

The cup wasn’t mine. The spill wasn’t mine. The embarrassment—that sure as hell was mine—because Lorraine, the CEO’s mother, not an employee, not a board member, just a walking antique purse with opinions, had snapped that order at me in front of our biggest client.

I didn’t say a word. I knelt—napkins, smile, pretend. That’s what you do when you’ve given fifteen years of your life to something and you’re not ready to watch it die stupid. But I knew right then, down in my knees on that hotel carpet, blotting up her tantrum, that something had cracked loose inside me. Not a break, a shift.

You want quiet? Fine. You want compliant? Done. But you forgot one thing, Lorraine. I remember everything. And I write it all down. Call it my hobby. Some folks crochet. I annotate power plays like they’re species in a damn field guide.

Hi, I’m Mary. I’m forty‑eight years old. I’ve got a Honda that rattles when I break, a desk drawer full of antacids, and one of those faces people assume is nice until I start using it. You’re probably listening while working or pretending to, and I get it—multitask away. But if this story makes your blood pressure rise the way mine did that day, go ahead and hit like, maybe even subscribe. Seriously, it keeps the team caffeinated and off each other’s throats. Otherwise, we start doing things like alphabetizing the printer paper.

Anyway, let me back up to when things still made a sliver of sense.

Northcross Partners started in a spare bedroom and a garage with no heat. Harold Northcross—God rest him—had the charm of Jimmy Stewart and the paranoia of a man who kept his passwords in a safe and then forgot the combination. But he was smart, knew people, trusted slow growth. When I joined, it was me, Harold, a guy named Bill who only lasted three months, and Harold’s dog, Jasper, who once peed on a banker’s briefcase during a pitch meeting. Good times.

I wasn’t flashy. Still ain’t. Never needed to be. My job was to listen better than the other guy and fix what clients didn’t know they’d screwed up. Harold used to say I was the thermostat in the room—kept things from freezing or burning down. He trusted me. Even made me interim lead the last time he had a health scare and needed to step back for a bit.

“Don’t let ’em sell the soul of the place while I’m out.”

And I didn’t. We weathered two economic hiccups, one client’s federal investigation, and a rebrand that looked like a toothpaste logo married a scarecrow. Through it all, I stayed. Harold stayed. The work stayed good.

Then Harold died. No warning. Just a call from his daughter saying,

“Dad passed in his sleep last night—peacefully.”

The kind of peaceful that lights a fire in every corner of your life. At the memorial, I wore black, brought flowers, and made myself useful. You know how it is. People mill around like grief tourists, and someone’s got to refill the damn coffee urns. That’s what Harold would have done.

Lorraine, meanwhile, fluttered around like she was auditioning for Dynasty, dabbing her dry eyes with a monogrammed handkerchief and reminding anyone within ten feet that her son would be stepping into Harold’s shoes.

Now, enter Devon. Devon Northcross—mid‑30s, expensive haircut, ego bigger than our quarterly revenue, and the emotional intelligence of a ham sandwich. I’d seen him hover around the business over the years, popping in during holidays or when his crypto portfolio dipped. He once asked me if we had an intern who could do his laundry because “this place should have full‑service vibes.”

He got named CEO in less time than it takes to update your LinkedIn bio. First week, he scheduled a “vision realignment” meeting. Translation: he used fifty buzzwords to say he didn’t like how things were run and wanted fresh energy. The board smiled like mannequins. Most of them owed Harold a debt or a golf win. None of them wanted to challenge the bloodline.

That’s when Lorraine started showing up. No title, no role, just there. She’d take Harold’s old seat in meetings like it was her birthright. Make comments like,

“That’s not very feminine,”

when reviewing my slide decks. Once she adjusted my collar before a video call. I asked her not to. She said,

“Just trying to help you look less… Ohio.”

I’m from Dayton. Bite me.

My first legacy client got reassigned within the month.

“We want to give Kevin a chance to spread his wings,” Devon said, referring to a guy who once CC’d the entire firm on a Chipotle order.

Fine. That’s the game. Play it slow. Be patient. Harold had prepped me for moments like this. Or so I thought.

I stayed professional. Rewrote decks Lorraine butchered with pink fonts and star emojis. Took meetings that got bumped from Devon’s schedule. Smiled when clients whispered,

“Wait, is she really his mom?”

Like we were in some weird sitcom. I even laughed once, but it started adding up. The snide remarks. The sudden “wellness check‑ins” from HR asking if I was feeling aligned. My annual review summary just said “could show more enthusiasm for new leadership.”

Then came the coffee.

That event was for our biggest account. Fifteen years we’d had them. Lorraine barreled in like she was hosting the Oscars. Manned the intern, fixed her slides, spilled her sugar bomb all over the carpet, and then, with the grace of a Bond villain, pointed at me and said,

“Clean that up.”

And I did. Then I stood and I walked. And I didn’t say a single word because my dignity may be dusty, but it ain’t dead.

They thought they were getting rid of the old guard. But what they didn’t know was that Harold once handed me a binder—thin leather, gold‑stamped—said,

“Just in case, kiddo. Don’t open it till you need it.”

That night I did, and the game changed.

The obituary was barely live when the vultures started circling in dress shoes and pastel blazers. Harold’s death hit like a tree falling in a forest—quiet, sudden, and no one quite ready to admit how much shade it used to provide. They held the emergency board meeting two days later. Not a week, not even long enough for Harold’s ashes to settle. Email came in at 7:03 a.m. Attendance required. Urgent succession planning.

I wore black. Devon wore a navy suit and the grin of a man who thinks the universe finally realized it owed him something. The board barely glanced at the bylaws before rubber‑stamping him. Continuity, they called it. Family legacy. Never mind that the only legacy Devon had was a half‑finished podcast about hustle culture and a T‑shirt line that said “grit is sexy” in Comic Sans.

“Dad always said this place could be more than just boring consulting,” Devon declared like he was delivering a TED talk no one asked for. “It’s time we stepped into the future.”

I didn’t say a word, just looked down at my notepad where I’d scribbled a single sentence: He never said that.

It didn’t take long for the real transformation to start. The front‑office TV stopped showing market news and started cycling through stock photos of people high‑fiving in open floor plans. The company newsletter began referring to employees as “change catalysts.” We were told to join daily standups even if we weren’t on the project because alignment is sacred. He even brought in a guy named Tyler—yes, just Tyler—to audit the vibe.

But the worst wasn’t Devon. It was Lorraine. Lorraine Northcross—previously known for her award‑winning apple butter and being banned from two HOA Facebook groups—suddenly became executive adviser to the CEO. Not on paper, not on the website, just in the room. Always in the damn room.

First, she popped into our Monday ops call. I assumed she was lost. By Friday, she was giving input on client deliverables.

“This font feels too serious,” she told me once while reviewing a budget breakdown. “Let’s give it some whimsy. People love whimsy.”

It was a risk‑mitigation report for a cybersecurity firm. Whimsy wasn’t on the menu.

She’d trail behind Devon during office walkthroughs, pointing at things like the coffee machine or the ficus and whispering. Next thing you know, we had a new machine that only made oat‑milk lattes and a ficus that shed like a nervous cat.

What stung wasn’t just the absurdity. It was the silence—mine. I didn’t push back when they reassigned the Becker account. I’d managed Becker’s portfolio since day one. We’d onboarded them in Harold’s garage. I’d flown to their headquarters during a snowstorm to help them navigate a merger, and now it was being handed to Greg, who thought EBITDA was a brand of combat.

“Greg’s got a modern edge,” Devon explained when I asked gently why I wasn’t included in the transition meeting. “Becker wants someone who understands the current market. No offense.”

No offense is always code for we think you’re old.

Then came the rebrand. Lorraine gathered the design team in the break room with a tray of Rice Krispies and said,

“Let’s make this logo more approachable.”

What followed was six weeks of pastel blobs and lowercase slogans. Our final draft looked like it belonged on a box of gluten‑free cereal.

I did my job. Rebuilt decks after her meddling. Smoothed things over when clients asked why an older woman with a Coach bag kept showing up unannounced. Smiled when Lorraine gave me unsolicited perfume samples with the note,

“This one’s youthful, but still humble.”

Each micro‑cut bled a little more. My title didn’t change, but the air around me did. Colleagues hesitated before looping me in. Projects I used to lead went quiet. Even the receptionist—God bless her—started saying,

“Let me check with Devon,”

when I asked for room bookings.

Still, I said nothing because people like me—we wait, we watch, we outlast the messes we weren’t allowed to name.

But the final gut punch came during the all‑hands meeting in Q2. I was standing near the back clutching a paper cup of watery coffee when Devon said it.

“This company used to run on legacy knowledge. Now it runs on boldness.”

Legacy, that word again. Code for outdated stalem.

Lorraine chimed in, voice syrupy‑sweet.

“And thank God we’ve got some fresh eyes in the room, right?”

She patted Devon’s arm and scanned the audience like a substitute teacher checking for note‑passing. No one looked at me, which was worse than anything else. They were already erasing me in real time.

Afterward, Becker’s VP pulled me aside.

“Mary, be honest,” he said, eyes darting. “Who is that woman?”

“Which one?” I asked—because I needed a second.

“The one in the yellow blouse with the clipboard. She said she’s head of strategy.”

“She’s not,” I replied.

“She’s what then?”

I took a long sip of my coffee and said, “She’s family.”

He nodded. “Ah. Say no more.” And he walked away.

That night, I stayed late to clean up my inbox and reorder some files. Lorraine passed by my desk on her way out, trailed by a perfume cloud and entitlement.

“Don’t work too hard,” she said. “You’re not getting any younger.”

She laughed—alone.

I stared at the screen a long time before opening a drawer I hadn’t touched in years. Inside, beneath a dusty binder clip and a dried‑out Sharpie, was the thing Harold had handed me five years ago. Leather‑bound, embossed. One phrase written in his sharp, spidery script on the inside cover: open only if the future forgets the past.

The edges were worn, the seals still unbroken. But the future—it had just forgotten me, and I was about to remind it who built the damn foundation.

I told myself it was just a phase—a long, stupid, humiliating phase—like puberty with name tags and passive‑aggressive email chains. You want to believe that if you keep your head down and do the work, the tide will turn. That someone in a blazer somewhere will suddenly remember you’re the reason our biggest accounts didn’t bolt when Harold took medical leave. That being quiet and competent would still mean something in a world now run by LinkedIn buzzwords and Lorraine’s Pinterest boards labeled “boss energy.”

Instead, I was gifted a front‑row seat to the circus.

Devon assembled a new “core innovation team,” which was just code for hiring people he’d met at a tech retreat where everyone wore matching hoodies and chanted about synergy. There was Austin, who described himself as a “thought alchemist.” Paige, who had two degrees in “organizational storytelling” and thought silence in meetings meant you’re not fully present. And Jace—just Jace—who once asked me if our legacy CRM could be converted into a blockchain interface because he read an article.

Devon assigned me to train them.

“Give them the download, Mary. You’re our institutional brain.”

I almost laughed—not because he was wrong, but because I knew that once my download was complete, they’d unplug me and toss the hard drive in a drawer.

Still, I trained them. I sat in conference rooms explaining account histories, project pitfalls, and why you never schedule client calls on Thursdays because Greg from legal always gets belligerent after midweek scotch tastings. They nodded, scribbled buzzwords, then launched a Slack channel called #NorthcrossRising, where they posted inspirational quotes and coconut water reviews.

Lorraine, meanwhile, started editing again. She’d waltz into the graphics department and hover behind interns, suggesting they add more sparkles to pie charts. She punched up one of my slide decks for a risk‑management client by adding clip art of a cartoon detective holding a magnifying glass.

When I gently asked her to revert it back, she replied,

“Don’t be so married to your work. It’s just pixels.”

I redid everything she touched—silently—cuz somewhere in the back of my mind, I still thought professionalism was my sword and shield.

Then came the Rogers call. Mr. Rogers (not that one) was the COO of a defense logistics firm. Big client, big temper. We’d been nurturing them for over a decade. We were mid‑presentation, Devon bumbling his way through a pitch Lorraine had bedazzled with flaming text transitions, when Mr. Rogers interrupted.

“Sorry, who is that woman again?”

He was pointing at Lorraine, who was seated at the end of the table, eating a tangerine mid‑call like we were in her damn kitchen.

“She’s, uh, family,” Devon said, fumbling. “She’s been advising me.”

Mr. Rogers narrowed his eyes. “She’s your mom.”

Devon nodded. Rogers went quiet for a beat, then muttered,

“Jesus Christ,”

and turned his camera off. The call ended early.

Afterward, Lorraine pouted.

“What crawled up his pants?”

Devon just said, “They’ll come around,” like gravity was optional.

The next few weeks blurred into one long slow bleed. A thousand paper cuts. Calendar invites where I was “optional.” Deliverables reviewed without my input. A client dinner I only learned about when I saw the photos on Instagram. Lorraine tagging herself as “corporate queen.”

Then came the gayla. Annual client appreciation gayla. Harold started it as a way to thank our long‑standing partners. Classy affair. Cocktails. Soft jazz. Plattered food that didn’t involve toothpicks or hummus fountains. I used to run the whole thing. Now I was handed a clipboard and told,

“Just help coordinate seating.”

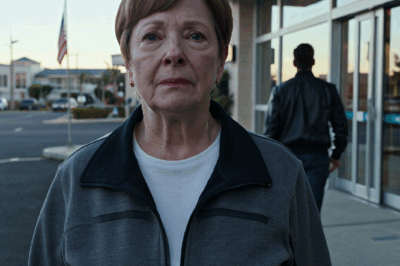

I wore navy. Lorraine wore sequins. Devon wore smugness. I stood by the bar managing the arrivals list when Lorraine sauntered up with a drink in one hand and her purse in the other.

“Oops,” she squealled—and a splash of sticky something hit the floor at my feet. “These waiters, I swear—”

There were no waiters near us. She looked down, then looked at me.

“Clean that up, would you?”

Just loud enough for the two VPs from our second‑largest account to hear. One of them raised his brows. The other took a sip of wine and watched me, and I—I bent down, grabbed a napkin, and cleaned.

I don’t remember the music or the clinking glasses. I just remember the sound of my own heartbeat roaring in my ears like a freight train I couldn’t jump off of. My hands were steady. My face was blank. But inside, something broke. Not shattered. Not messy. Just snapped like a circuit flipped. A light turned off.

I didn’t say a word. Didn’t even stand up quickly. I finished wiping, tossed the napkin into the bus bin, and nodded like it was just another task in the long list of things that are beneath me but expected anyway. Lorraine had already turned her back.

Later that night, I drove home in silence. No music, no podcasts—just the sound of the highway and my own thoughts screaming through the noise. When I got home, I went to the hallway closet, dug past the spare batteries and the earthquake kit and the emergency lint roller. Pulled out a fireproof box.

Inside was the binder—Harold’s binder. I hadn’t opened it yet, but I stared at it a long, long time because the woman in sequins might have spilled her drink, but I was about to spill the truth.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t rage either. I just changed my clothes. That night, after scrubbing the scent of gayla olives and sour humiliation off my skin, I pulled on sweatpants and an old college hoodie with a hole in the elbow. No wine, no ice cream, no pity party—just me, the lamp on the dining table, and the fireproof lock box that had sat unopened for five years under a box labeled “holiday lights (broken).”

I spun the dial on the lock. It clicked open with the low metallic groan of something that hadn’t been disturbed in far too long. Inside, it was exactly as I remembered: a slim black binder with a single gold‑embossed title on the spine—contingency clauses. No subtitle, no explanation. Just those two words—and a yellow Post‑it on the cover that said, in Harold’s handwriting: for Mary, when it’s no longer yours, but you remember whose it was.

I sat down. Opened it.

Each one was a scanned copy of Northcross Partners’s original articles of incorporation. Filed the same year Harold’s hair still had color and our only office had a dog bed in the corner. I flipped slowly at first, then faster. Past equity tables, share classes, voting structures.

Then I saw it.

Section seven: founders reversion clause. It wasn’t highlighted. It wasn’t bold. It was just there like a trap door in a church floor—beautifully buried and ready. The language was dense. Harold never used ten words when thirty would do. But I’d seen enough legalese in my time to parse the bones of it.

In the event of incapacitation, death, or sustained absence of the founding officer, and upon documented breach of charter principles—namely governance, integrity, non‑discrimination, and conflict‑of‑interest policy—named successor trustee shall be granted temporary authority to assume control of the founder’s class of voting shares and seat for a period not to exceed 180 days or until remedial action is verified by the board.

My eyes skipped back: named successor trustee—Mary E. Wallace.

I sat back in my chair, didn’t breathe for a full ten seconds. Then I leaned forward again and read the clause three more times. The details were clear—clear enough, at least. If the company’s governance had become compromised through nepotism or hostile practices, and if I could prove it, I could—under Northcross’s own founding charter—trigger a temporary leadership override. Not to become CEO, not to install myself like a vengeful monarch, but to take back the founder’s seat temporarily—long enough to clean house, long enough to rip the sequined rot out of the walls.

I stood, walked to the kitchen, brewed a pot of black coffee so strong it could strip paint, sat back down, and began the real work.

By 10:45 p.m., I’d made three copies of the clause, highlighted every line that mattered, cross‑referenced the charter violations, labeled a new folder: supporting evidence. I printed emails, Slack screenshots, calendar removals, meeting reassignments—even photos of Lorraine giving feedback on internal deliverables: unsigned, unapproved, and uninvited. Pulled up her LinkedIn—she’d finally made one—and screenshotted the part where she listed herself as “strategic adviser at Northcross Partners.” No listing in our payroll. No board approval. But there she was, claiming influence. That alone was a violation. Harold’s charter forbade family advisory roles without written consent of majority stakeholders. That was rule #3.

I dug deeper, found a photo from the gayla—the one where she pointed at the mess I wiped. In the background, two senior clients watching, one with his arms crossed. I started a log: hostile environment indicators. Beneath it, I listed every time I’d been publicly undermined, reassigned without explanation, or gaslit into smiling through demotion. Each entry had a date, a timestamp, a witness.

I texted no one. Called no one. This wasn’t a group project.

By 1:12 a.m., I had three manila folders filled, labeled, and paper‑clipped. I drafted a one‑page summary addressed to the firm’s general counsel, a man named Baxter, who still owed me a favor for saving his ass during a client meltdown back in 2017. I printed two copies, signed and dated them, and sealed one in a courier envelope. Then I sat back and looked at my work. It was meticulous, clinical, cold—but it burned in my hands like a secret weapon.

Some women throw wine. Some scream in stairwells. Some quit in the middle of a meeting and post about it on Facebook. Me, I file paperwork—because there’s a special kind of vengeance in doing things correctly. In making sure every i is dotted, every t crossed so that when the moment comes—and I knew it would—there is no argument, no loophole, no escape hatch. There’s just truth: documented, timestamped, legal. And Harold, wherever he was, had made sure that when this company lost its way, someone who actually gave a damn would have the keys to bring it home.

By 3:37 a.m., the sun was starting to whisper along the edges of the blinds. I poured the last of the coffee, placed the sealed envelope by the front door, and sat with Harold’s binder in my lap. Tomorrow, they’d try to fire me, and I would let them—because they didn’t know what I knew. They didn’t see what I saw, and they had no idea that the woman they thought was already gone was about to walk right back in, holding the contract and the match.

The sun had barely peeled itself over the horizon when I hit send on the courier order. Next day, priority. Signature required. Delivery window: 9:00–9:15 a.m. Not a minute sooner, not a minute late. I timed it to collide perfectly with my own funeral. Sorry, HR meeting. They thought I was coming to be buried. I was coming to bury them in paperwork.

But I wasn’t stupid. Before I fired my one legal bullet, I needed a second set of eyes. Not just any eyes—his.

Franklin Bellamy hadn’t set foot in the Northcross building in nearly a decade. Harold’s old general counsel—half‑shaved, silver beard, hands that always trembled a little, and a voice like every clause came with a curse. Last I’d heard, he was living in a retirement condo near Lake Erie with a rescue cat named Winston and a deep hatred for modern yogurt.

I still had his number—buried in my ancient contacts list under: Frank (Do not call unless on fire).

So I called and said one sentence.

“Harold’s clause just came alive.”

Silence, then a quiet, dry chuckle.

“Meet me at Murray’s. Bring strong coffee and all your sins.”

Murray’s diner hadn’t changed. Same cracked leather booths. Same waitress with the chain‑smoking rasp who called everyone “hon” whether you were four or ninety. I slid into the back booth at 7:03 a.m., binder in hand, folders tucked into a plain black bag, and two coffees—both black, both no‑nonsense.

Frank arrived in a tweed jacket with elbow patches and eyes sharper than most of the boardroom buffoons I’d dealt with in the last six months.

“You look like someone about to commit a legal homicide,” he said, sitting down without a hello.

“Good,” I replied. “Because I’m not asking if I can. I’m asking if I’m right.”

I handed him the binder—open to section seven. He read silently, lips barely moving. Every few seconds he’d grunt, a low, irritated sound—like a man discovering someone had been rearranging his chessboard while he slept. Then he looked up.

“They used this once,” he said. “Early days. Harold’s cousin tried to sneak in a buddy from B‑school as interim CFO. Board ignored protocol. Harold flipped this clause like a switch. Shut it all down in seventy‑two hours. Reinstated the bylaws, fired the cousin, froze everyone’s shares for a week just to remind them who owned the damn skeleton key.”

“So it holds if you’ve got the documentation?”

I pulled out the folders, slid them across the sticky table. One for governance violations. One for hostile work environment. One for unapproved executive interference. Frank flipped through photos, timestamps, Lorraine’s self‑appointed adviser LinkedIn listing. Meeting invites with her name but no formal role. Emails where she gave directives. Lorraine’s calendar entry for “executive strategy sync” with no one else invited. Even a Slack message where she called me “emotionally territorial about the past.”

Frank snorted.

“That’s a bingo.”

“And this.” I slid over the email removing me from the Becker account; an internal message chain where Devon says, “Mary’s got too much history. Let’s freshen the optics.”

Frank’s smile was slow and mean. “Optics just killed him.”

We sat in silence for a beat, sipping our bitter coffee as the hum of the diner buzzed around us—plates clattering, forks scraping, the occasional hiss of bacon. Frank finally leaned back.

“You’re the named trustee. They’re in violation. You’re within your rights to trigger the clause. But once that courier walks in, you don’t get to un‑pull the pin.”

“I don’t want to,” I said it flatly.

He nodded once. “Then mail the grenade.”

Back at home, I rechecked everything. Three times. The envelope was thick. I sealed it with reinforced tape, printed the summary letter again, initialed the bottom corner in blue ink, added one final page with my notarized affidavit confirming the events, dates, and actions taken by both Devon and Lorraine over the last ninety days.

I emailed Baxter, our corporate counsel. The subject line just read: governance clarification for review at 9:00 a.m. Attached was nothing—just one line in the body: “Hard copy arriving via bonded courier. Please confirm receipt in person.”

Then I printed one more copy for myself. Labeled it “in case of fire” and tucked it in my glove compartment.

The calm that settled over me wasn’t loud. It wasn’t even satisfying. It was the quiet hum you hear right before a storm breaks. I went through the motions of the rest of my morning like I was setting a table for someone else’s dinner. Fed the cat, washed my mug, put on my blazer—charcoal gray, nothing flashy, just enough shoulder structure to say don’t.

At 8:34 a.m., I left the house. At 8:59, I stepped off the elevator onto the Northcross executive floor. I passed Lorraine in the hallway. She gave me a look like I was a coffee stain she meant to bleach out of the rug months ago.

“Big meeting today,” she chirped. “Try not to make it about you, dear.”

I smiled.

“Wouldn’t dream of it.”

She walked past. I kept walking. At 9:00 a.m. sharp, the courier would hand Baxter an envelope that would split this place open like a bad zipper. And I’d be sitting in the next room, waiting for my scripted execution. Calm as still water. Because you can’t fire the fire alarm. You can only wait for it to go off.

It was a Tuesday. Gray sky, stale coffee. The kind of day that settles in your bones before you’ve even made it past the copier. I knew what was coming. Not because someone tipped me off or because the stars aligned in my cereal bowl. No, I knew because Devon was the kind of man who thought retribution worked best before noon—while the coffee was still hot and the egos hadn’t curdled yet.

HR email landed at 7:52 a.m. Subject line: discussion regarding workplace conduct. Attendance required. Time: 9:00 a.m. Location: Executive Conf. Room B. No details, no context—just enough vagueness to make an intern sweat through their undershirt.

But I wasn’t sweating.

I arrived early. Devon, of course, arrived late—smelling like Tom Ford and poor decision‑making. Lorraine was already seated when I walked in, perched like a discount duchess in her floral scarf and talon‑red nails, sipping tea from her own damn mug—gold‑rimmed, probably brought from home because corporate dishware gave her hives. The HR rep was new, just out of grad school probably. She looked like she still believed in company culture. Her name tag said “Nicole,” and she wouldn’t meet my eyes. She looked like someone had handed her a live grenade and told her it was a stress ball.

“Mary,” Devon said, settling into the seat across from me like he was hosting a fireside chat. “Thanks for joining us. This won’t take long.”

Lorraine smiled without showing teeth.

“It’s so important to hold space for accountability.”

Devon glanced at Nicole, who fumbled with a folder and a company‑branded pen.

“Let’s keep this simple,” he said, cracking his knuckles like he was doing us all a favor. “Your attitude has become a drain on morale. Clients have noticed. Leadership has noticed. You’ve been resistant to change, dismissive of team strategy, and, frankly, insubordinate.”

He said the last word like it tasted expensive.

I raised an eyebrow. Didn’t speak. Didn’t blink.

Nicole shuffled some papers.

“Uh, based on the documentation provided by senior leadership, this qualifies as grounds for… um… termination under section 12.4 of our employee conduct policy.”

Devon leaned back, lacing his fingers behind his head like some frat god on a throne of borrowed power.

“So,” he said, “effective immediately. You’re terminated from your position at Northcross Partners.”

Lorraine was already pulling something out of her tote. A sad little envelope with my name on it printed in Comic Sans. Probably thought that font softened the blow.

Still, I said nothing.

Nicole cleared her throat.

“You’ll have thirty minutes to collect your things. Your system access will be disabled at 9:30. Security is on standby. Just standard protocol.”

Lorraine spoke again, voice dipped in condescension syrup.

“We appreciate your years of service, dear. This is just the natural evolution of things.”

I looked at her. Really looked at her. This was the woman who spilled drinks on purpose, who gave me perfume samples labeled “hopeful,” who once asked if I could smile more during presentations because it’s good for brand warmth.

Devon looked pleased—like a child who just knocked over a sandcastle and expected applause.

“Well,” he said, “anything you want to say?”

I almost laughed—not because it was funny, but because of the sheer perfect timing of it all. Because just then, just as the sentence “you’re terminated” fully settled into the air like cheap cologne, there was a knock at the door. Three knocks. Firm, rhythmic.

Nicole flinched. Devon frowned. Lorraine squinted like someone had mispronounced her wine label.

The door opened, and in stepped a man in a crisp gray uniform, black leather pouch under one arm, courier badge on his chest. He scanned the room, clipboard in hand.

“I have a delivery for Mr. Baxter. Legal counsel. Time‑sensitive.”

Nicole stood halfway, flustered.

“Oh. Uh, he’s just next door, I think.”

“No worries,” the courier said—already moving toward the adjacent conference room. He didn’t wait for permission.

Devon shifted in his chair.

“What’s that about?”

“Probably just more legal red tape,” Lorraine muttered.

I looked down at my watch. 9:03 a.m. Right on time.

Still, I didn’t say a word—just placed my company badge on the table. Next to it, a small velvet box containing the service pin I’d received at the ten‑year anniversary party where Harold gave a speech. Devon was too busy scrolling on his phone to clap.

Nicole reached for the envelope with shaking fingers, as if unsure who should touch it first. I pushed it gently toward her.

“Don’t worry,” I said, voice calm as winter wind. “You won’t need that.”

And with that, I stood, smoothed my blazer, walked to the door—didn’t look back—because I didn’t need to explain myself to the wreckage. The building was already on fire, and the sprinkler system just got its activation notice.

Baxter was the kind of lawyer who carried two pens at all times and spoke in perfectly punctuated sentences. He also hated surprises—detested them, really. Once called an impromptu birthday party a “hostile ambush,” so when the courier handed him a heavy sealed envelope marked private legal matter for immediate review, he didn’t open it right away. He stared at it first as if gauging the weight of its consequences through the paper. Then, with the efficiency of a man who’d red‑lined his own wedding vows, he slid it open with a letter opener shaped like a sword. Only Baxter.

I wasn’t in the room anymore, but the sequence of events spread like the scent of burned toast—fast, sour, and impossible to ignore.

Lorraine was still in the HR conference room when Baxter entered. Devon was mid‑boast, telling Nicole to get facilities to repurpose Mary’s office—maybe for a juice bar or “creative nap zone.” Nicole just blinked.

Baxter didn’t sit. He didn’t speak. Just walked in, holding the envelope in one hand and the letter inside it in the other. His eyes scanned the first page quickly, then more slowly. Then he turned the page.

Silence. More silence. Then that small, subtle act of dread: he adjusted his glasses.

Devon didn’t notice. He was busy smirking at his own cleverness. Lorraine, however, sensed the shift. She glanced at Baxter and said,

“What’s the delay?”

Baxter looked up, and for the first time since Harold’s death, there was a crack in the legal armor of the firm. His voice was steady, but his face betrayed him—creased at the brow, corners of his mouth pulled tight like someone trying not to spit out a mouthful of pennies.

“Sir,” he said—and the word landed like a pin drop in a funeral parlor. “She just triggered the founder’s reversion clause.”

Devon blinked.

“The what clause?”

Baxter turned the page again, held it up between two fingers.

“Section seven of the founding charter. Filed at incorporation. Verified, notarized, and last amended five years ago.”

Lorraine scoffed.

“That’s nonsense. That’s just some ceremonial fluff Harold had written up when we were still faxing things. It’s not enforceable.”

“It’s enforceable,” Baxter said quietly. “It was ratified twice.”

Nicole—poor thing—looked like she was trying to melt into her ergonomic chair.

Devon leaned forward.

“Okay, even if it’s real—which, for the record, I’m calling BS—how does that affect anything now?”

Baxter raised his eyes.

“The clause is explicit. In the event of the founder’s death, if governance is compromised by nepotism or conduct that violates charter principles, the founder’s voting rights revert temporarily to a named trustee.”

He held up the letter again.

“That trustee,” he said, “is Mary E. Wallace.”

Lorraine made a noise somewhere between a cough and a laugh.

“What? ‘Cause she found an old binder in a shoebox? Come on, this is just Mary being dramatic. It won’t hold up.”

Baxter didn’t respond. He didn’t have to. He simply stepped aside as another figure entered the room quietly, efficiently—like a weather front. It was Carol, the board secretary. Clipboard in hand, face unreadable.

“We’ve confirmed the signature and timestamp,” she said, addressing the room. “The trustee designation is valid. A review has been scheduled for immediate emergency session.”

Devon shot to his feet.

“No, no, no. You can’t just— She’s not even with the company anymore. We literally just fired her.”

“Which,” Carol didn’t flinch, “per the clause may be construed as retaliatory action against a protected trustee. That alone qualifies as a procedural breach.”

Lorraine clutched her mug like it was a life preserver.

“This is absurd.”

But Devon—he finally looked scared. He looked like a man who just discovered the lock he changed didn’t work on the one person he thought he’d locked out.

“You’re saying she has power?” he asked, voice thin now.

“No,” Baxter replied, folding the letter and placing it in his briefcase with precision. “I’m saying she is power. For the next 180 days.”

A long, hot silence draped itself across the room like a suffocating curtain. Then came the final blow. Baxter opened his laptop.

“Per clause procedure, Miss Wallace’s authority includes the ability to place senior executives on temporary administrative leave pending governance review.”

He looked up.

“Shall I draft the notice, or would you prefer to do it yourself?”

Devon’s mouth opened. Nothing came out. Lorraine finally put her mug down. And for the first time since she slithered into this company like a scented virus, she didn’t have a single word.

I didn’t sit at the head of the table. That would have looked too eager, too hungry—and I wasn’t here to claw at power. I was here to restore it. So I picked the second seat on the right, the one Harold used to call the quiet anchor. It faced the window. Let in light. Let you watch the shadows move while others pretended not to feel them.

Baxter stood at the end of the room, folder in one hand, glasses perched low on his nose. His expression was unreadable, but I saw the way he tapped the corner of the paper—one, two, three times. That was his tell. He only did that before he read something that would end someone’s career.

Lorraine was already adjusting her blouse like this was a lunch meeting. Devon—sweating through his collar despite the AC being set to meat locker—tried smirking like the cameras were still on.

Baxter didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t need to.

“Sir,” he said to Devon. “She just triggered the founder’s reversion clause.”

The words dropped like wet concrete. Devon blinked twice.

“What the hell is that?”

Baxter didn’t answer with a summary. He didn’t soften it. He just flipped open the folder, cleared his throat, and began reading aloud.

“Section seven: In the event of incapacitation or death of the founding officer, should hostile governance or breach of the non‑interference principles occur, the founder’s class of controlling shares and governance rights may revert to a designated trustee for a period not exceeding 180 days, or until board‑led review is completed.”

He glanced up.

“In this case, the designated trustee is Mary E. Wallace.”

The room didn’t gasp. Not at first. It just went still—like it was holding its breath for someone to say, “Just kidding.” But no one did.

Devon looked at Lorraine like she might swoop in and swat the clause away like a fly. She opened her mouth.

“I’d advise you not to interrupt,” Baxter said, eyes never leaving the page.

Lorraine shut it again. Fast.

Baxter continued.

“This clause was reaffirmed in a board memo dated April 14, 2020. It includes language explicitly forbidding nepotism, including familial advisory roles, executive interference by non‑employees, and retaliatory action against the trustee. All three have been documented.”

Carol—ever silent—clicked her pen and started scribbling notes. Her face was like a gravestone.

“The trustee, in this case, retains full proxy rights over the founder’s governance vote,” Baxter continued. “Effective immediately. This includes the right to call emergency sessions, initiate leave of absence for current executives, and revoke advisory privileges of non‑elected personnel.”

News

I Bought A Mansion In Secret, Then Caught My Daughter-In-Law Giving A Tour To Her Family: ‘The Master Suite Is Mine, My Mom Can Have The Room Next Door.’ What They Captured

Nobody saw this coming. Three months earlier, my life looked completely different. I was Margaret Stevens, sixty-three years old, recently…

‘This Is Emma,’ My Mother-In-Law Announced Proudly At Christmas Dinner As She Gestured Toward A Perfectly Dressed Blonde Sitting Beside Her. ‘She’ll be perfect for James — once the divorce is final.’

This is Emma, my mother-in-law announced proudly at Christmas dinner as she gestured toward a perfectly dressed blonde sitting beside…

My Son Laughed At My ‘Small Savings’ — Until The Bank Manager Asked To Speak With The Main Account Holder — Clearly Saying My Name.

The morning my son laughed at me began like any other quiet Tuesday on our street — the kind where…

My Daughter Got Married, Still Doesn’t Know I Inherited $7 Million—Thank God I Kept It A Secret.

The air in my Charleston kitchen was still thick with the ghost scent of wedding cake and wilted gardenias. I…

I Drove 600 Miles to Surprise My Daughter—Then, in Front of Everyone, She Pointed at Me and Said, ‘You Need to Leave.’

My name is Genevieve St. Clair, and at sixty‑eight, my life was a quiet testament to a mother’s enduring love….

I Bought A Luxury Condo Without Telling My Parents. Then, At Lunch, Mom Said, “We Know About Your Apartment, And Your Sister Is Going To Move In With You.” I Pretended Not To Care, But Two Weeks Later, When They All Showed Up… BAM! A LOUD SURPRISE!

I signed the closing documents on a Tuesday afternoon in March, my hands steady despite the magnitude of what I…

End of content

No more pages to load